IN THE MINDS EYE by Paul Roberts

This DEBUSSY CENTENARY article was first published by International Piano, March/April 2018

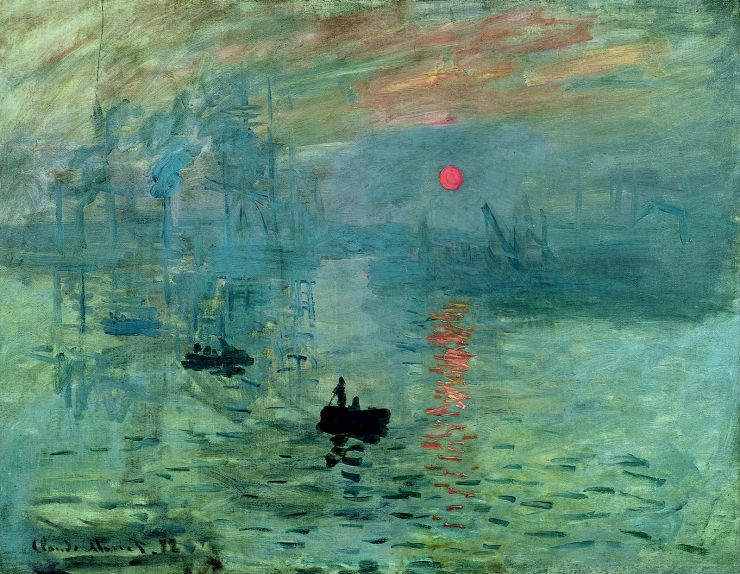

Dawn of Impressionism:

Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872)

The term ‘Impressionism’ is a crude label to apply to the music of Debussy, whose compositions, while often inspired by visual motifs, defy definition as they strive to capture the essence of reality rather than merely a vague sense of mood. Paul Roberts describes how Debussy used his ears and eyes to provoke a complex, fresh and imaginative response to the world through the medium of sound.

DEBUSSY WAS DISMISSIVE of the labels that contemporaries attached to his music: ‘Impressionism and Symbolism, useful terms of abuse,’ he declared. Of his orchestral Images, certainly one of those works that might justify the Impressionist tag, he wrote ‘I am trying to do “something different” – realities, in a way – what imbeciles call “impressionism”.’ A century after Debussy’s death, does the debate over Impressionism still have any resonance? Are conductors, performers, pianists, students and music lovers enlightened by the term, or befogged by it? Without doubt the Impressionist label is difficult to dislodge – but then that might just be the nature of labels.

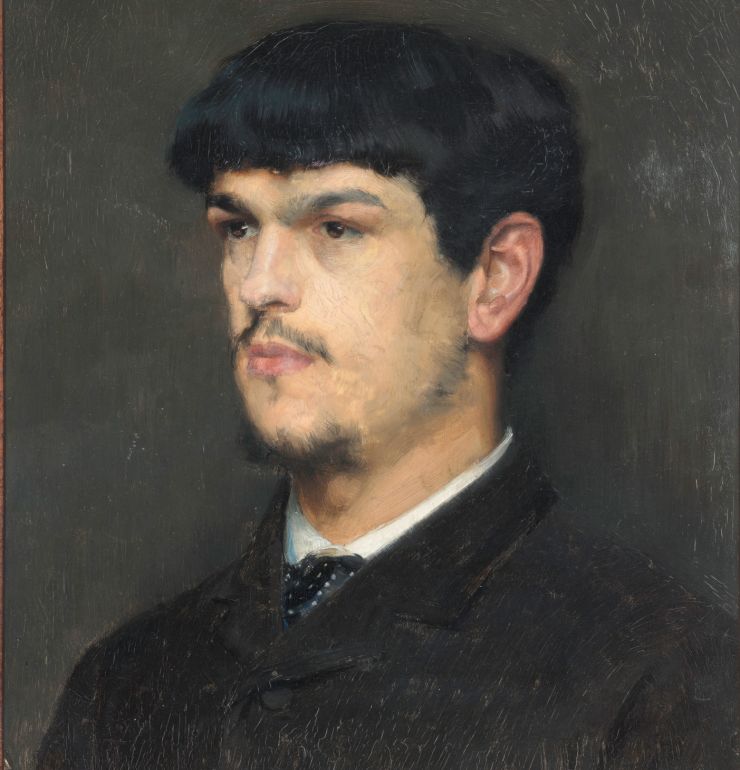

Claude Debussy: ‘I love pictures almost as much as music’.

Portrait by Marcel-André Baschet (1894)

It is worth recalling its origin. The ‘useful term of abuse’ was indeed just that in the 1870s when the critics first got their teeth into the early generation of Impressionist painters, Monet, Pissaro, Renoir et al. In 1874 their first exhibition was greeted with such derision in the press that crowds flocked to the gallery – to laugh. The paintings were ridiculed because they looked unfinished and unskilled, a slapdash assemblage, according to numerous critics, of ‘palette scrapings’ and ‘black tongue-lickings’. Monet’s painting of Le Havre at sunrise provided the catalyst: ‘I couldn’t really call it a view,’ he wrote later, ‘so when it came to be catalogued I said “put Impression”.’ And ‘impression’ stuck like a barnacle, a perfect way of describing what was deemed a sketch, not a properly serious and solemn painting worthy of high art.

Impressionism soon became the word to denote the outrageousness of any ‘modern’ art, of whatever genre. Thus a report on one of Debussy’s student compositions could declare: ‘One has the feeling of musical colour exaggerated to the point where it causes the composer to forget the importance of precise construction and form. It is to be strongly hoped that he will guard against this vague impressionism, which is one of the most dangerous enemies of truth in works of art.’ He didn’t. The work was Printemps (for orchestra and chorus), and the report on it offers several straws in the wind, not only the celebrated word. Excessive colour and apparent lack of structure were a warning of things to come.

Even Debussy’s first instrumental masterpiece, the String Quartet, could provoke the comparison: ‘It is more like a hallucination than a dream,’ wrote one critic. ‘Is it music? Perhaps, but only insofar as the canvases of the neo-Japanese of Montmartre [the Impressionists] can be called paintings.’ The writer even uses the term ‘musical pointilisme’, an allusion to the paintings of Georges Seurat that were produced with a myriad of coloured dots. And Debussy’s songs, Proses lyriques, in the same concert, displayed ‘a defect of the auditory sense similar to the defect of sight responsible for the distorted vision of certain painters.’

The extraordinary fact is that at this date, 1892, Debussy had not published a single piece of instrumental music with a descriptive title, not a hint of those works to come in which visual images abound. The orchestral Nocturnes and Images, the sea symphony La mer, and those exotically titled piano pieces such as ‘Gardens in the Rain’, ’Reflections in the Water’, ‘The Moon Sets Behind the Temple that Was’, ‘Golden Fish’ – all these were some 10 or more years in the future.

One phenomenon in particular had provided the critics with their ammunition it lay to hand in the very venue where the String Quartet was heard, an art exhibition promoted by a leading European avant- garde organisation, La Libre Esthétique in Brussels. On the walls, in full view during the concert (an all-Debussy event) were paintings by the original Impressionists, Pissaro, Renoir and Sisley, and the new generation including Gauguin, Redon, James Ensor and Toulouse-Lautrec. By such conjunctions are myths derived and labels embedded. Debussy’s music, undoubtedly modernist to the ear, became forever associated with the extraordinary provocations of modernist visual art. He had not intended it, yet he could hardly avoid it.

Let us shine a light on this historical moment from another angle. I want to suggest that Debussy was just as keenly stimulated by the paintings in Brussels as his critics, but in the opposite direction. We know that he was well up on the new developments in visual art: ‘I love pictures almost as much as music,’ he once wrote. He adored and collected Japanese colour prints, which were a huge influence on Impressionist painting; and he was acquainted personally with painters such as Maurice Denis, Lautrec, the Symbolist Odilon Redon and Paul Gauguin, as well as the flamboyant American James McNeil Whistler.

Debussy belonged to the avant- garde milieu that was endlessly debating the relationships between painting, poetry and music. He frequently attended the famous Mardis of Stéphane Mallarmé, the weekly Tuesday gatherings where the venerable Symbolist poet would expound his views on poetry and art, not least his view of the Impressionists. In a seminal essay on Edouard Manet and his followers, Mallarmé was one of the first to articulatethe startling originality of the new painting and its revolutionary impact. It is well attested by contemporary sources that Debussy had a highly developed visual imagination. Soon after his Brussels concert he embarked on a modest set of piano pieces entitled Images – the first instance of his use of this title – which he dedicated to the daughter of his close friend, the painter Henri Lerolle, also a friend of Degas and Renoir. (Renoir did a portrait of Yvonne Lerolle and her sister Christine at the piano. In the background are paintings by Degas.) In the event these early Images, now known as Images oubliées, remained unpublished until 1977. But the visual reference stayed in Debussy’s mind and gave birth to the three magnificent sets of Images in the first decade of the 20th century. Of the first book of Images for piano, he commented – with perception and no lack of modesty – that it would take its place ‘to the left of Schumann and to the right of Chopin.’

Around the time of the Brussels concert, Debussy was also experimenting with what he called ‘finding the different combinations possible inside a single colour, as a painter might make a study in grey.’ He toyed with this experiment for several years, and in 1899 it finally became the haunting ‘Nuages’ (Clouds) of the Nocturnes for orchestra. Whistler had already used the title Nocturnes for a series of twilit landscapes and seascapes, and commentators were quick to draw comparisons: Debussy now became ‘the Whistler of music’. In a programme note for the first performance Debussy wrote that the title Nocturnes was intended to convey ‘all the various impressions and the effects of light that the word suggests.’ ‘Nuages’ suggested ‘grey tones, lightly tinged with white’.

Faced with such evidence it is difficult not to argue that there is a strong association, in some meaningful sense, between Debussy’s music and visual art. Pianists can recognise the imaginative truth of ‘grey tones lightly tinged with white’ in such Preludes as ‘Brouillards’, and ‘Voiles’. ‘Brouillards’ (Mists), is an intricate but seemingly effortless conjunction of bitonality and harmonic instability that perfectly parallels the moods and tones of certain Monet paintings, or indeed the Nocturnes of Whistler. ‘Voiles’ (Sails), with its whole-tone contrapuntal structure, creates a similar effect by different means musically Debussy never repeats himself. Here the visual reference is to the emptiness of a seascape with distant sails. Debussy would have known the small seascape pastels of Degas, the painter whom of all the Impressionists he admired the most. Gaugin said, ‘Colour is vibration just as music is.’ I am reminded of these words every time I play the opening pages of the Prelude ‘La cathédrale engloutie’ – one of the most programmatic of Debussy’s pieces which culminate in the instruction ‘gradually coming out of the mist’.

The piece begins with an arresting evocation of a calm grey sea at dawn from which eventually the cathedral will terrifyingly arise (terrifying in the way fairy stories are benignly terrifying). Debussy’s art conveys here, as so often, a sense of suspended time akin to the motionlessness of a painting. There is a similar instruction for the unearthly resonances of ‘Cloches à travers les feuilles’, from Images Book II, marked ‘like an iridescent mist’ (but, again, a different harmonic palette). That Debussy did not wish to be labelled an ‘Impressionist’ cannot alter the facts of the visual associations we are repeatedly invited to make.

Across the whole Debussy oeuvre, the pianist especially is the principal recipient of a richly endowed repertoire of ‘impressionist’ images: Estampes (1903), L’isle joyeuse (1904), Images I and Images II (1904-08), Children’s Corner (1908) and on to the two books of Préludes of 1910 and 1913. For many pianists, exploring the context of the descriptive titles – and they can be literary as well as visual – provides an essential frame for interpretation. (I am reminded of Claudio Arrau’s insistence that he had to read the whole of Dickens’s Pickwick Papers as preparation for performing ‘Hommage à S Pickwick Esq’, the slightest of all the Préludes.)

The title Estampes alludes to the coloured prints of the Japanese woodcut artists, which Debussy knew so well, and also to the highly stylised poster art of Lautrec and Jules Chéret, which was such a feature of contemporary Parisian entertainment and night life. The pianist might imagine taking possession of three vivid coloured prints from three regions of the world: ‘Pagodes’, inspired by the exoticisms of the Javanese gamelan; ‘Soirée dans Grenade’, alluding to Spanish flamenco dancing and singing; and ‘Jardins sous la pluie’, a Japanese woodcut scene of cherry blossom and rain, viewed through a French lens (Debussy quotes two French nursery songs). The first book of Images opens with the magnificent ‘Reflets dans l’eau’, surely related to the ubiquitous paintings of water beloved by the Impressionists (as well as to Liszt’s water pieces ‘Au bord d’une source’ and ‘Jeux d’eaux à La Ville d’Este’: Debussy heard Liszt perform the first of these when he was a student in Rome, the year before Liszt died). The second book of Images ends with the superbly luminous ‘Poissons d’Or’, inspired by a Japanese lacquer painting Debussy owned. It is one of his finest pianistic creations, an extraordinary tour de force of virtuosity and harmonic and melodic audacity.

Debussy’s Préludes were his last essays in Impressionism, before he changed direction with his Études in 1915 (a work of genius which needs another article all of of its own). The titles invite us into an exotic world of landscapes and seascapes, winds and storms, Spanish and Italian narratives, oriental mysticism, clowning, ragtime and fairy stories, rounded off with a firework display – all the subjects of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting. Debussy, always enigmatic, secretive, passionately protective of the essence of music, now places the titles at the end of each piece, in brackets: so we don’t have to pay attention to the image, he is saying. The music is all. (‘Music is not just the expression of a feeling,’ he once wrote, ‘it is the feeling itself’.) Of course this disclaimer can only work once. When we reach the end of the piece and learn the title, in our mind’s eye we forever after place it at the front. And surely these titles enrich our imaginative experience, just as they did the composer’s.

Debussy had read the philosopher Schopenhauer and would have known his views on the nature of music. ‘The point of comparison between music and the world lies hidden very deep,’ wrote Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation.

But the effect of music is far more powerful and penetrates far more deeply than that of the other arts; for they communicate only shadows, whereas music communicates the essence.’

Debussy’s luminous ‘Poisson d’or’ was inspired by this Japanese lacquer panel from the composer’s collection

There is no better way of grasping the intention of Debussy’s so-called ‘Impressionist’ music than these words, which he would have believed ardently. ‘With all my heart I believe that Music remains for all time the finest means of expression we have,’ he wrote, echoing Schopenhauer.

Debussy’s titles, whether placed at the end or not, are intended to take the listener inside the music, not outside it. The titles are above all designed to provoke an intensity of listening. In his Préludes and Images Debussy distilled and communicated some of the essence of the external world, touching the core of human experience and the way we express as well as process this experience through music. We have no way of knowing whether he knew the words of the 18th- century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, from the first Dictionnaire de Musique, but we can confidently say he would have approved: ‘Music portrays everything, even those objects that are purely visible. By means of almost inconceivable powers it seems to give the ear eyes.’

Pianist Paul Roberts is a leading authority on French piano music and the author of Images: The Piano Music of Claude Debussy. He will be giving numerous recitals, lectures and master classes during the Debussy anniversary year in the UK and the United States, including the Menuhin School (21/22 Feb), Santa Cruz (18 Mar), University of Washington, Seattle (2 Apr), Guildhall School of Music & Drama, Milton Court (3 Jul) and the London Piano Festival (6 Oct). www.paulrobertspiano.com